Join the Team as a Wildlife Friendly Fence Technician!

Applications Open Until Filled

General Description:

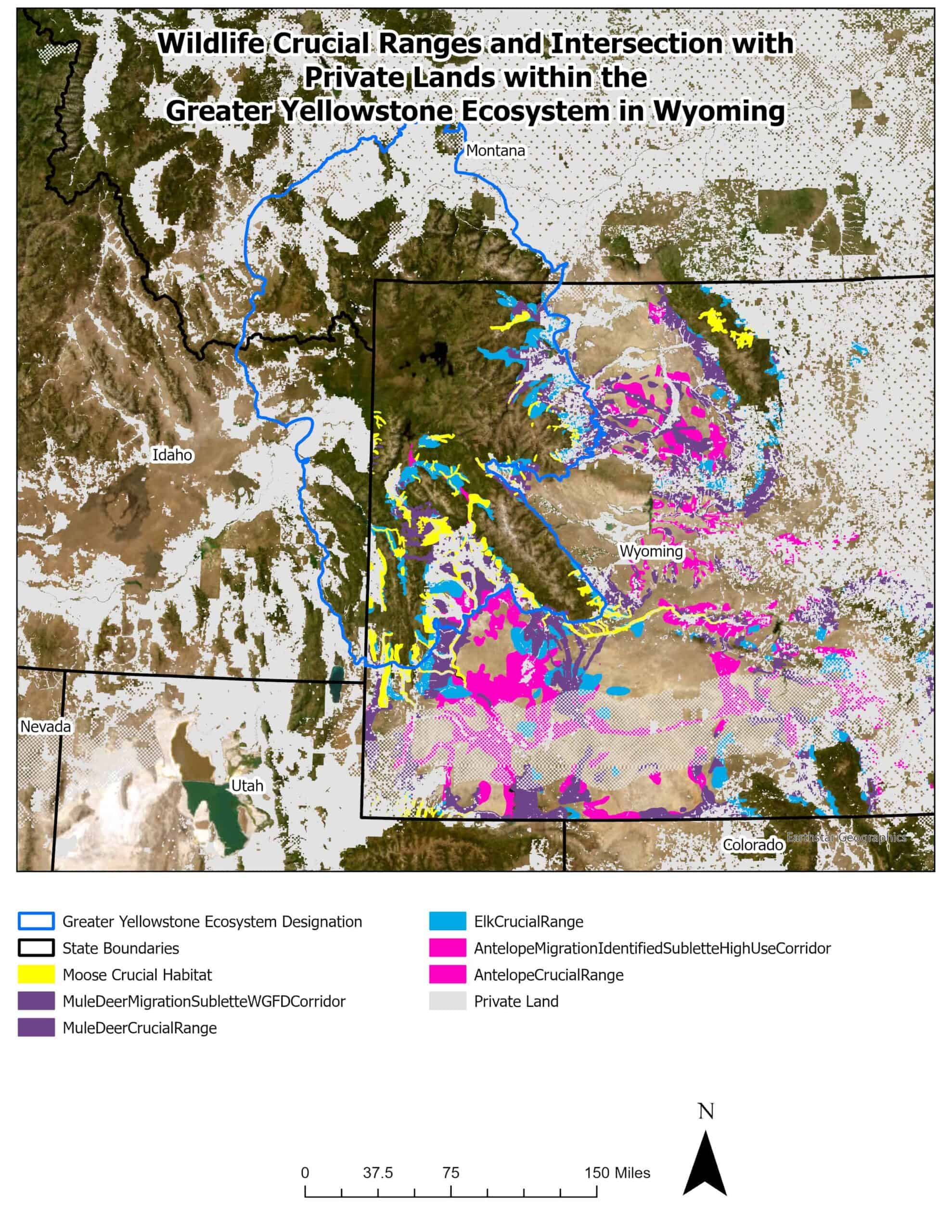

The Ricketts Conservation Foundation, in partnership with the Upper Green Fence Initiative, seeks a Wildlife Friendly Fence Technician based in Bondurant, Wyoming. This position will support the efforts of the Wyoming Game and Fish Fence Program Manager and the Upper Green Fence Initiative. This position will be responsible for fence inventory which will inform future removal or conversion to configurations more suitable for wildlife. This work will expand upon an already high producing program that has funding, partnerships and landowners eager to do projects. Extensive presence in the field is necessary across a large area ranging from the Hoback Basin and the Upper Green River Basin to the Red Desert in Carbon, Fremont, Sublette, and Sweetwater Counties. This position will require the development of working relationships with other Ricketts Conservation Foundation employees, Wyoming Game and Fish employees, other state and federal agency personnel, local landowners, sportspersons, and non-governmental organizations to identify and implement fence improvement projects across all land ownerships within priority wildlife habitats.

Essential Functions:

The listed functions are illustrative only and are not intended to describe every function which may be performed at the job level.

- Inventory existing fences within the project area and utilize this data to prioritize fences for modification, removal, etc.

- Develop organized work schedules.

- Compile, edit, and disseminate reports and information.

- Respond to landowner requests and assist private landowners and public land managers.

- Work with minimal supervision in remote locations, difficult terrain, and in all types of weather for extended periods of time.

Knowledge & Skills:

- Strong written and verbal inter-personal communication skills.

- Understanding of different fence types, materials, installation techniques, and construction methods.

- Knowledge of rangeland management practices.

- Ability to manage projects with minimal supervision and work independently.

- Experience working alone in remote locations and navigating with the use of a handheld GPS, OnX or other mapping applications such as Avenza or Field Maps.

- Identifying and resolving problems that may arise during project execution.

- Experience using, manipulating, and digitizing GIS or KML data for the purpose of creating maps, final reports, and project identification.

- Skilled in the operation of 4x4 vehicles, ATV’s and the proper use of trucks and trailers in all types of road and environmental conditions.

Minimum Qualifications:

Education: High school diploma or equivalent. Preference will be given to those pursuing a degree in wildlife, range, ecology, biology or closely related field.

**Must have a valid driver’s license.

Experience: Preference will be given to those with 1 to 2 field seasons of field experience demonstrating the knowledge and skills identified above.

Physical Working Conditions:

- Be able to work in various weather conditions and environments.

- Work away from the duty station for extended periods of time.

- Ability to safely operate motorized equipment, including 4x4 pickup truck, and ATVs.

- Ability to lift 50 pounds or more.

Position & Application Detail:

Duty Station: Bondurant, Wyoming

Housing: On-site housing or housing allowance provided.

Pay & Benefits: Wage $15.00 per hour. Relocation expenses paid up to $400. Phone compensation is $25.00 per month.

Duration: Position starts May 18th, 2026, and ends August 22nd, 2026

Applications: Applications will be reviewed starting March 1, 2026. Position is open until it is filled.

Please email your letter of interest, resume, and three references to Shari Meeks at [email protected]. Incomplete applications will not be considered.